How Netflix can end the Hollywood strike in a way Disney can’t afford

Striking Writers Guild of America (WGA) members walk the picket line in front of Netflix offices as SAG-AFTRA union announced it had agreed to a ‘last-minute request’ by the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers for federal mediation, but it refused to again extend its existing labor contract past the 11:59 p.m. Wednesday negotiating deadline, in Los Angeles, California, U.S., July 12, 2023.

Mike Blake | Reuters

Netflix earnings report on Wednesday sent its stock down, but the first question on the company’s post-earnings Wall Street analyst call cut to the chase of Hollywood’s biggest issue: Will the world’s biggest video-streaming company let Hollywood’s ongoing strikes by writers and actors interrupt its business, just as the company is turning into a true profit machine? Some analysts are quietly suggesting that Netflix won’t.

Even as most people focus on the fact that Netflix has big inventory of content that could let it ride out a long strike, its burgeoning financials suggest another possibility: That Netflix will, in months to come, drive a nascent streaming industry where nearly all of its rivals lose money toward a deal that Netflix can afford but rivals can’t.

Netflix spent years tolerating losses and, later, burning cash to build up its library of Netflix-produced content, betting on the day when it would get big enough to generate big returns on that investment. The second-quarter results released Wednesday are the least of it. The most bullish analysts on Wall Street think profits could more than double by 2025, with even average estimates saying profits will rise to $8.3 billion from $4.5 billion last year. After the report, Evercore ISI analyst Mark Mahaney estimated that Netflix would earn $25 a share in 2025, at the current share count, more than $11 billion.

Now, analysts speculate that Netflix will, in months to come, force a settlement to the strikes by the Writers Guild of America and Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists before its rivals so it can get back to business. Their theory isn’t based on inside information, but on the inexorable logic that Netflix’s expected profit surge will simply overwhelm its share of the costs of settling the strikes, giving co-CEOs Ted Sarandos and Greg Peters different incentives than legacy players like Disney and Paramount Global, and tech rivals including Amazon.

“Netflix is likely to position itself to be seen as [friendly] to the actors,” Wedbush Securities analyst Michael Pachter said. “It’s kind of perverse that Netflix is in the AMPTP [Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, the group negotiating for studios],” he said. “The right solution is to do whatever is best for Netflix.”

For the second quarter, Netflix reported adding 5.9 million subscribers, generating a slightly-below-expectations revenue gain of 2.7% and well-above forecast profit of $3.29 a share. Its stock has been volatile around earnings reports in the past, since it frequently gets rewarded big for beating estimates and punished for narrow misses. Its shares were down by as much as 6% on Thursday morning.

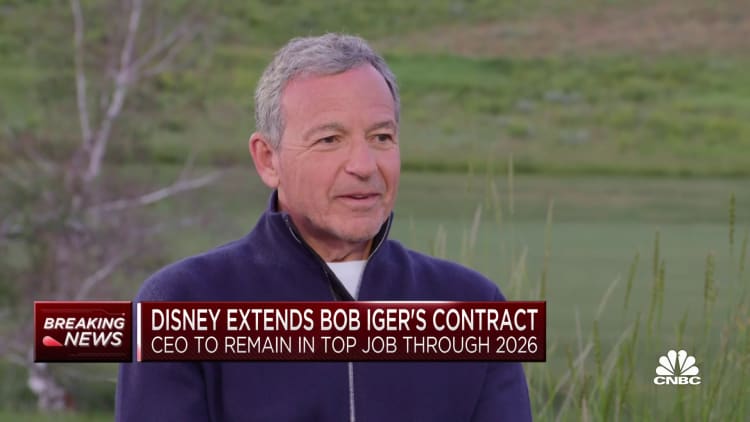

The war of words from the studios turned ugly last week, with an article in the trade Deadline quoting an anonymous studio executive as saying executives planned to squeeze the unions until members gave in out of fear of losing their homes, on issues led by residual payments to artists for streaming programs as they are reused. That was followed by a CNBC interview in which Walt Disney Co. chairman Robert Iger said the unions’ demands were unrealistic and add to the problems of a film-and-TV industry not yet recovered from the Covid pandemic.

“There’s a level of expectation that they have that is just not realistic and they are adding to a set of challenges that this business is already facing that is quite frankly very disruptive and dangerous,” Iger told CNBC’s David Faber at the annual Sun Valley conference.

Netflix spent its earnings call sending a strikingly different message, with co-chief executive Ted Sarandos bringing up his family history as the son of a union electrician who joined strikes “on more than one occasion” and saying it wants an equitable deal as soon as possible.

“The strike is not something we wanted,” said Sarandos, whose company is negotiating jointly with competing movie studios like Disney and Paramount whose parent companies also own streaming services. “We make deals all the time. We are at the table constantly. I was raised in a union household.”

The leverage equation is not as simple as big, rich companies starving poor workers, since major streaming services other than Netflix all lose money or barely break even like Warner Bros. Discovery‘s HBO’s Max service. Some big-media companies that own streaming services, like Paramount and Disney, have seen their shares drop even in the renewed bull market of the past year.

LightShed Partners analyst Rich Greenfield says Netflix made $6.5 billion last year excluding interest, taxes, and non-cash charges, while rival streaming services at Paramount, Disney and NBC lost more than $8 billion. The culprit: The high costs of making new programs. Mahaney says Netflix’s annual EBITDA will hit $12 billion in two years.

How much settling on artists’ terms will cost Hollywood

Settling the strike on the artists terms would make programming even more expensive, but Netflix said in May that it did not expect a deal with writers to materially affect its profits. (Actors had not yet scheduled their strike). The bond-rating agency Moody’s Investors Service puts the potential tab to settle both strikes, along with a new contract with directors, at $450 million to $600 million a year. That’s a relatively small number for an industry with revenues topping $70 billion, $31.6 billion of it last year at Netflix. But studios are digging in partly because most of the industry is already struggling.

Moody’s numbers are consistent with a statement from the Writers’ Guild of America saying its proposals for expanded residuals, higher pay and adjustments in compensation schemes to account for the fact that streaming shows have shorter seasons with fewer episodes, would cost producers $429 million a year, or $86 million more than management’s counter-offers.

WGA did not respond to interview requests. The Screen Actors’ Guild hasn’t released any such estimates, and the joint negotiating arm of the studios did not make a spokesperson available for comment.

Netflix spokesman Jake Urbanski declined comment for this story.

Moody’s report shows why a deal with the artists won’t dent Netflix. The company’s roughly one-third share works out to $150 to $200 million, less than 50 cents per Netflix share, or about 3% to 5% of last year’s profit and less than 4% of what analysts project for this year. Indeed, it’s about the same as compensation for Netflix’s top five executives, about $160 million last year. Netflix shareholders voted down its executive compensation plan in an advisory vote this month, as the WGA said on Twitter that its leaders’ pay exceeds the cost of the union’s proposals.

New Netflix efforts to make money

Aside from executive pay, Netflix has a series of plans in the works that will recover the cost of any settlement many times over.

The company’s new crackdown on password sharing is likely to boost earnings, Mark Mahaney said in a note to clients. And its initiative to offer a lower-priced plan that includes advertisements, reversing two decades of resisting ads as the company has seen subscriber growth mature, will add $3 billion in high-margin revenue by 2025, Mahaney projected.

Indeed, advertising revenue dominated the discussion on Netflix’s earnings call, with executives saying that the $3 billion estimate will eventually prove too low, and suggesting the dollars they are targeting are now spent on so-called “linear TV” networks, which happen to be owned by streaming rivals they are battling, a pool of money Peters called “a sweet spot we can speak to right now” as it builds the technology to compete with highly targeted online ad sellers.

“We wouldn’t spend all this effort, time and effort if we didn’t think it could be at least 10% of revenue,” Netfix chief financial officer Spencer Neumann said. “That’s a bar we’re shooting for to meet or beat over time. There are a lot of branded TV ad dollars we have set our sights on over time because we think we’re a great ecosystem…Our goal is to be a better-than-TV model.”

Netflix’s robust health stands in contrast to its rivals. On top of Disney’s Disney+ losses, its growth reversed in the most recent quarter as it moved to cut spending, helping to prompt a 9% drop in Disney shares. The Hulu service it co-owns with Comcast saw its operating profit (which Disney did not break out) drop in the quarter ending April 1, Disney said, and has also seen growth peter out. Paramount Global’s Paramount+ service lost $1.8 billion last year, but saw losses shrink in the first quarter. Comcast has said it expects to lose $3 billion on its Peacock streaming service this year.

Where Amazon, Apple stand in streaming

Profitability is harder to discern at Amazon’s Prime Video Service and Apple‘s Apple+ TV, whose parent companies report their results as part of larger divisions. Amazon reported spending $16.6 billion on producing movies, music and TV shows last year, virtually the same as Netflix’s $16.7 billion, while Apple spent about $7 billion.

Netflix closed the first quarter with 232.5 million subscribers, making them the only one to crack a threshold of 200 million that has proven to be a threshold for meaningful profitability, Pachter said.

At the same time, the media players have many other issues to fix in their old-media assets, Moody’s analyst Neil Begley said. Disney may be open to selling its ABC and ESPN divisions, which have lost viewers and revenue to cord-cutting and viewers spending more time on streaming platforms. Paramount slashed its quarterly dividend to a nickel from 25 cents in May after its traditional TV businesses, including the CBS Network and Nickelodeon, saw first-quarter revenue drop 8%.

“Netflix already ditched its legacy business,” renting DVDs through the mail, Begley said. “The others are trying to fix their cars while driving 50 mph. They’re under enormous pressure from Wall Street, from their boardrooms,” he added.

The problems in other businesses, and the lack of scale, both make it harder for the old-media rivals to add more costs, like bigger residuals for writers and actors, than it is for Netflix, Pachter said.

“Disney’s ability to continue propping up loss-leading businesses is part of this,” Lumley said. “People wonder if Paramount could become an acquisition target. Netflix does seem to be the top of the pack [because] they don’t have pressure from underperforming traditional businesses.”

That may mean all the studios, including Netflix, dial back on the number of shows they greenlight in order to pay artists better, Moody’s Begley said. The victims after the eventual settlement will be people who make marginal shows, Pachter said, with a barb at “the third season of Santa Clarita Diet,” a black comedy on Netflix about suburban cannibalism starring Drew Barrymore, as content consumers won’t miss.

And that leaves Netflix an opening to force deals that only it, among the streamers, can easily afford, Lumley and Pachter said, especially as customers begin to notice the absence of new content, first on traditional TV and later on streaming. The hardball tactic, if Netflix deploys it, would be to step in as the artists’ friend and prod rivals toward a deal only it can easily afford, Pachter added.

“Ted Sarandos shows up at every awards show and sits with actors,” Pachter said. “He wants to be seen as simpatico.”

Disclosure: Comcast is the parent company of NBCUniversal, which includes CNBC.