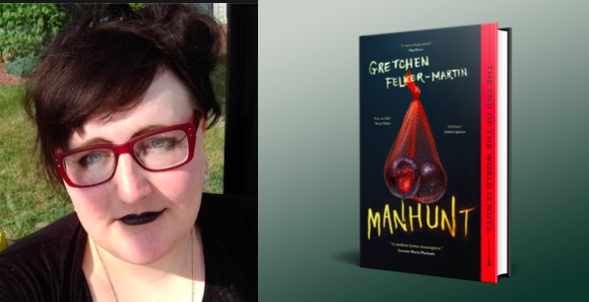

Manhunt Author Gretchen Felker-Martin on Apocalyptic Body Horror

Last year, Gretchen Felker-Martin unleashed her debut novel, Manhunt, upon the world. Set in a post-apocalyptic near future in which a virus is turning testosterone-heavy people into mindless, cannibalistic rapists, Manhunt follows Beth and Fran, two trans women, as they hunt men to harvest their organs for estrogen in an effort to remain uninfected.

Their closest friend and ally, a cis woman named Indi, is a fertility specialist who processes the estrogen from the organs of dead cis men. Joining the group, albeit reluctantly, is Robbie, a trans man who, up until this point, has been lone wolf-ing it. Together, the group fights for survival against both rabid cis men and a TERF (trans-exclusionary radical feminist) militia group that is systematically hunting and killing trans people.

Manhunt rocked the horror lit scene, with readers and critics praising the author for her evocative prose, fresh take on the apocalypse survival genre, and beautifully crafted and unflinchingly grotesque scenes of carnage.

We caught up with Gretchen Felker-Martin for a chat about Manhunt, queer and trans representation in horror, and her upcoming novel, Cuckoo.

Dread Central: What came first when you were first conceptualizing Manhunt? Plot or characters?

Gretchen Felker-Martin: The plot idea came to me first, and then I sat down and hashed out the people that I wanted to explore it with.

DC: Was there an inciting incident? What spawned this?

GFM: As a kid, one of my favorite stories was Alice Sheldon’s “The Screwfly Solution”, which is a similar sort of gender apocalypse where overnight, every man in the world becomes a homicidal rapist. They’re still fully aware and sentient, but they suddenly can’t repress their urges to commit violence against the women around them. A friend reread it to me three or four years ago, and it was just like lightning hit the back of my brain.

There’s so much in this story that just by its nature, because of the way it’s designed, is totally off the map. There are a million people having entire lives in the wreckage of this that have never been written about. And I really wanted to get into that.

DC: What was your research process like?

GFM: I did quite a bit. I think the thing that I had to spend the most time on was the shelf lives of various foods and drugs. And also the amount of certain commodities in the United States, like, how many domesticated pigs do we have? How much glass is there in the U.S. in raw terms at any given time? A lot of this stuff is super hard to find out and buried in a bunch of numbers, but it was really interesting. For instance, I learned that maple syrup can stay shelf stable in a glass container in the dark for over 200 years.

I think the single hardest thing was learning about fertility treatments and determining the sex of embryos. Not only is it incredibly tedious and way outside my wheelhouse, but you have to find a way to write it without making the reader fall asleep. Who wants to talk about microscope settings?

DC: Did you read any TERF-written material?

GFM: Yes. Some I had already read. I read The Transsexual Empire years ago. Janice Raymond is actually a background character in the novel as part of the TERF hierarchy in Maryland. Revisiting that was not pleasant, but it was informative. I also read a fair number of TERF articles, and I skimmed a couple of recent books like Irreversible Damage. Mostly what I felt at the end of all of that research was that TERFs are idiots. They have nothing of value to give to the world. Nothing at all.

DC: Speaking of TERFs, were you expecting such a backlash about that part in the book where J.K. Rowling dies off-screen?

GFM: I’ll be honest, I did. I thought that as soon as someone found it and screen-capped it, I would be in for a miserable world of hurt. I thought about taking it out, and then I realized that it would probably be really good for the book. And I also thought it was funny and wanted to keep it in. I had kind of a stressful week with tabloids picking it up and going nuts, but the book did great. It was great for us, overall. So you know, fuck ‘em. Free advertising.

DC: Are there any scenes in Manhunt that you regret? And alternatively, are there any scenes that didn’t make the cut?

GFM: I think if I were to go back and pick the whole thing apart again, there are a few small moments where I might change a build-up or a line. I think that Robbie makes the switch from being a total loner to caring about the world too quickly. But there’s nothing I really regret.

The only scene [in Manhunt] that we cut really deserved to be cut. It was kind of tasteless. It was a horribly tacky forced impregnation scene in the bunker. And it just didn’t need to be there. My editor, Kelly Lonesome over at Tor Nightfire, was correct. She’s wonderful to work with.

DC: Are any Manhunt characters based on any public figures or anyone in your life?

GFM: Yeah, for sure. To me, Teach—the TERF antagonist—is very much a synthesis of Jordan Peterson and Elizabeth Holmes. This charismatic huckster figure who’s kind of pathetic but just never stops the hustle. Always living inside this palpably false persona and getting all of her self-actualizations by leeching off of teenagers and younger women who are insecure and want a mother figure. And then various trans characters are based on friends and exes and family to an extent, but it’s all fictional.

DC: In the TERF sections, there was a vibe of political lesbianism. Was that intentional?

GFM: It’s definitely something I was aware of going in, and the sexlessness of a lot of the TERF higher-ups proceeds from that. Political lesbianism has given us many of the worst feminists in the entire world. It’s a complete dead end. And it proceeds almost without variation from really regressive, reactionary ideas about sexuality and sex: that women shouldn’t be having it, that it’s bad to enjoy it, that it’s disgusting for a woman to be horny, that it’s violent for a woman to desire another woman.

It’s like this hermetically sealed-off sexuality where you sit side-by-side in your matching khakis with your buzzcuts and drive your Subaru to Whole Foods together, and that’s it. There’s no actual desire in it.

DC: Teach’s protégée Ramona grapples with her own sexual desires—what was the inspiration for her character?

GFM: Ramona was really interesting to write. I didn’t include her in the narrative until I got about a third of the way through and ended the first part of the book. And then I realized that this book really does need a TERF character.

So I based her off a client I had when I was a sex worker who was an absolute fucking nightmare. She was a huge closeted chaser who was, as far as I know, straight, married, but obsessed with trans women. And in session, she would be both worshipful and controlling, and really emotionally obsessive, but there was no sense that any of those emotions were meant for me. She was having this whole thing in her head, and I was the sex toy that enabled her to do it. Even though I needed the money, I eventually stopped seeing her because it was just so noxious to be in the same room with her.

But she was the seed that Ramona grew from—this person who needs trans femininity in her life to be sexually fulfilled, to feel attraction and love, but whose relationship to trans femininity is abusive and controlling and hateful, and she refuses to unpack that intersection of awful things in her own brain. Ramona is morally lazy. She does whatever is easiest in her context. She’s sort of the ideal Nazi—she doesn’t really have any principles.

DC: Can you talk about how sex work is explored and presented in Manhunt?

GFM: Sex work in the world of Manhunt is pretty volatile and difficult and vulnerable, much like sex work in our world. I think that when you remove men from the social context, there is all of this sexual and interpersonal stuff to unpack in their absence. How do women relate sexually to each other? How does the sexuality of straight women function in this world? And so you have this massive rearrangement of hierarchies of desirability and what traits that you want in a sex worker. Suddenly you have this market for masculine-looking trans women which is something I’ve seen repeatedly in porn and sex work as a field.

A lot of people want trans women to be visually freakish and they really get off on the sideshow aspect of it. I wanted to bring that across in the narrative, the ways in which trans women are still consciously and subconsciously treated like men by the cis women around them, and the indignity of being less than a man but forever a man in the eyes of the people that hate you.

DC: Do you think there’s a parallel with trans men?

GFM: Yeah, but I think that the dynamic is different. We don’t see trans men quite as threatening as we do trans women. There are many ways in which they face awful oppression and violence and brutality. But it’s a different equation, fundamentally.

I think that trans men in the world of Manhunt are highly sexually desirable to cis women around them. But at the same time, they’re cut off from testosterone and a lot of other masculinizing activities.

DC: In Manhunt, there’s a lot of privilege around physical attractiveness. How did that enter the plot?

GFM: The hierarchy of beauty was something that I had on my mind right from the start. I think that it informs so much of life in communities where survival is tenuous. If you’re not just beautiful, but beautiful in a way that the dominant culture values, there’s a living to be made as a beautiful example of your subculture who is palatable to mainstream culture. And, of course, conversely, if you aren’t, there isn’t. And so you have to negotiate that space, working twice as hard for half the reward, and also dealing with the emotional reality of it, because it’s not something anyone can really control.

I think that those things are very seldom addressed with seriousness in horror. But the basis of body horror is that we know our bodies are mutable, and we both fear and long for them to change drastically.

The hierarchy of beauty also plays into things that I wanted to talk about with regard to assimilationism—the desire of a subculture to join the mainstream and abandon its own identity and values. When you are physically palatable to the world around you, you have the freedom to leave queerness in a lot of ways [and] enjoy the benefits of straightness and cisness.

I think that creates really understandable, compelling conflicts for people. In [Manhunt], Fran wants to disappear into the world around her, and she might be able to. It’s tremendously compelling to her because she wouldn’t be hunted anymore. She wouldn’t be despised. Who doesn’t want that? We all want that. Her sin isn’t wanting those things. It’s the fact that she forgets about the people who can’t have them.

DC: The owner of the bunker, Sophie, was dangling the possibility of assimilation in front of Fran.

GFM: To me, Sophie represents…not quite a chaser figure. She’s definitely interested in queerness, aesthetically, and wants to be fashionable the way that queers are fashionable. But queers aren’t quite people to her, in the same way that poor people aren’t quite people to her. And I think that’s something you run into a lot if you mix circles with people who grew up with money. You encounter a ton of unchallenged suppositions about who is and isn’t fully human, and the first time that you find concrete proof of that, it’s very disorienting and frightening. You realize that someone who might even love you genuinely does not fully see you as a person.

I wanted to get that across with Sophie. And of course, her family’s money comes from tech. She’s the living remnant of Silicon Valley as well as being indicative of our capacity to just ruin any situation. Here we have some security from an incredibly dangerous world, and of course, it has to be a miserable hierarchy where you’re beholden to a 20-something with the moral sensibilities of a nine-year-old.

I really have very little respect for the rich, which is why Sophie isn’t so complicated. I don’t think the rich are complicated; I think they’re mostly stupid, greedy, and evil. And also very unhappy. And so unimaginative. I mean, what is the thing that Sophie wants so badly that she destroys herself? It’s to have a baby with her boyfriend. It sucks. That’s such a shitty fucking goal.

DC: For her, the baby is just another prop.

GFM: Yeah, absolutely. An accessory. She has no interest in being a mother.

DC: Indi, as the doctor she hires to help her conceive, also seems like a prop for her.

GFM: Indi, I think, is the character who’s most personal to me. You know, her body is like mine, her experience of life shares a lot with mine. It was really hard to give myself permission to write her because there’s this strong sense you learn that people like you do not belong in books. And at least for me, I spent years self-policing. ‘You can’t write about fat people, you can’t write about that. No one wants to read it. It’s rude, it’s gross.’ And so it felt very vulnerable to write this character and to let myself be on the page in that way. That was really emotionally intense and difficult.

DC: It was really interesting and refreshing how in Manhunt, all the targeted and conscious violence was perpetuated by women.

GFM: What I really wanted to get across with this [Manhunt] is that when you take men out of the equation without changing the culture, women just step into their roles. When we see things like Hillary Clinton as Secretary of State getting celebrated, or the first woman Rear Admiral in the Marines, it’s like, why on earth would we celebrate that? That’s horrible. All we’re doing is stepping into the patriarchal world that pre-existed. We’re not changing anything or fixing the lives of other women downstream. We’re just deciding who has their hand over the button. No one should have that power. That’s the actual thing you need to deconstruct before you can make meaningful progress.

DC: Would you describe yourself as a feminist?

GFM: Yes, absolutely. I have no illusions about feminism’s purity or even its potential to change the world. We’ve seen multiple waves of it brought down by the racism that is baked into it, and the ableism and fatphobia and other extensions of this patriarchal culture that we refuse to unpack, but I do consider myself a feminist. I do believe, of course, as a woman, that women are people and deserve all the rights that people have. We are as fully human as anyone else. And beyond that, I would say that integral to my feminism is an understanding that the way that America exists, the way that world powers exist in general, is wrong and has to stop. I consider my feminism pretty inextricable from my socialism.

DC: What does being a woman in horror mean to you, if anything?

GFM: To me being a woman in horror is largely about my relationship to my body and my relationship to various conceptions of womanhood throughout history. And these are things that I’ve been so focused on for my entire life, that I’ve spent years and years sort of pressed up against the most unpleasant aspects of them or the parts that have the most friction with my existence. And I feel like to really vent that friction, fiction is the best outlet. It gives me a sense of perspective and control.

And I also take a tremendous amount of comfort in being part of a lineage of women in horror. Shirley Jackson, Melanie Tem, Daphne du Maurier, although “woman” is debatable; her kids suppressed a bunch of stuff about her masculine persona.

Overall, I have to say I was really surprised by the way that fellow authors welcomed me. I was never a writing group, writing culture kind of person, so I didn’t have a lot of exposure to other authors. When I came into horror, like right away, Chris Golden and Brian Keene, all of these older guys who already have really established careers, were immediately just so kind and welcoming to me, and so incredibly supportive of my work and really personally interested [in me]. It was overwhelming how warm and ready for me they were.

DC: Would you say you feel more connected to horror as a creator or as a spectator?

GFM: Definitely both. I watch horror movies pretty much every day.

DC: Do you have any favorites?

GFM: Oh absolutely. The Devils, Black Christmas, Under The Skin, Possession…the 1973 Wicker Man is one of my favorite movies. I loved Brandon Cronenberg’s Possessor. I love Cronenberg—Crash and Dead Ringers and Videodrome…all of it really. I’m a horror movie fanatic.

DC: How do you feel about the state of trans representation in horror?

GFM: It’s nice to see it increase measurably in my lifetime, even on a year-to-year basis. It’s really exciting to read books with trans protagonists. I feel really disappointed by how white it is so far. I would love to see more trans women of color both on the page and especially behind it. Of course, getting into that, you have to start considering the economic realities of America and all of the opportunities that trans women of color are denied just because their labor is totally occupied with staying alive.

DC: On a broader level, how do you feel about current queer representation?

GFM: In horror, I would say I’m quite into it. I don’t love the movies that straight people make about the “issue of the week” horror stuff. There’s this sense of being marketed to that I find kind of repugnant. But at the same time, it’s nice to go to the movie theater and see someone at least a little bit like you up on the screen. It’s exciting! I try not to spend too much time pissing on that parade. I do think that there’s some importance to representation. What it is, is good and nourishing to see and experience; what it isn’t is real societal change.

DC: Are there any references or nuances in Manhunt that cis and/or straight readers wouldn’t get?

GFM: There’s a lot of stuff in there that straight people wouldn’t get, like the sort of complicated ways that trans women with different appearances relate to each other. Stuff about the intersection between fatness and queerness, and the archetype of the fat lesbian. All of those things are not things that I expect straight readers to get.

And really, I wasn’t trying to help them. You know, when straight people pick up the book and tell me they loved it, I’m like, ‘That’s great! Awesome! But you know, I didn’t write it for you.’ There’s so little that’s just for us. This is just for us.

DC: Is there anything you wish you were asked more about in interviews?

GFM: I very seldom get asked about fatness in my writing and in horror in general, which is something I’m very interested in and passionate about. I think it’s really under-explored. Like womanhood, the state of fatness is one of being in forced proximity with your body image for a long time, and dealing with tremendous amounts of both exterior and interior pressure to not be what you are—to physically shrink, to change your appearance.

This is all the stuff that body horror is made up of, and yet, when we see fatness and horror, it’s either a punch line or it’s to denote that someone is pitiful. This past year, we had maybe the second horror movie ever to star a fat woman in a non-horrible way—Piggy.

Then when you move into post-apocalyptic horror, I think there are all these other layers, like how focused on physical capability that genre is. It almost always sort of quietly assumes that everyone undesirable in the world, everyone fat or ugly or disabled, was just swept away in the initial wave, whatever it was, and now we don’t have to think about them. And so when I write, I want to write about those people.

DC: Can you tell us anything about your upcoming novel, Cuckoo?

GFM: Cuckoo is about a group of queer children in the mid-’90s who are sent to a conversion therapy camp in Utah. When they get there, they discover that something is creating copies of the children and sending these copies, who are well-behaved and cis and straight, back home to their parents. And so the story is about these children navigating their own emerging identities and figuring out who they are as teenagers, and then coming face-to-face with this thing that is remaking them for its own purposes.

Cuckoo hits the shelves in January 2024.