What if ‘Scream VII’ Went This Way? It Might Work

I was asked recently, as an animal person, how I feel about the killer animal genre. First, let me explain “animal person.” Like many, I’ve always had a tender heart for animals but, in 2003, I saw a film that completely changed how I viewed human/animal relationships. The film, Fast Food Nation, is not a part of the genre I’m going to talk about here, but it kickstarted the feelings that would lead to this article. From there, I have tried my best to learn about animals, treat them respectfully, and avoid exploitation as much as possible. My feelings towards killer animal movies shifted. It didn’t disappear, it just changed a little. How? Well, it’s a complicated relationship.

As a kid, my grandfather never missed a chance to sit me down in front of Monstervision with Joe Bob Briggs or his favorite Harryhausen film. I got accustomed to seeing humans as food for dinosaurs and every strange creature imaginable really quickly. The idea of a monster eating you was the most horrible thing I could think of as a child. Truly the stuff of nightmares. So, naturally I gravitated towards it.

When you took this idea away from the fantastical creatures and applied it to something like a shark it became even scarier to me. Sharks exist. Alligators exist. You can’t reason with them. They aren’t even doing it out of some deeper evil or hate of the human race. They are just hungry, and nature can be a ruthless thing. These animals live everywhere, the sea, the swamp, the mountains. The idea that you could be on vacation and find yourself in the coils of an anaconda or in the claws of a grizzly is one that has kept humans terrified since the beginning of time.

It’s interesting to see how storytellers turn these animals into monsters and how that can inform your feelings about their work. I think your relationship with animals and your beliefs on the treatment of animals definitely influences your feelings on the matter, but I also believe both extremes can coexist. At a certain point in my life, I became more aware of the plight of animals, you get to a point where when you watch some of these movies and you’re rooting for them more than the human characters.

I noticed there were certain stories where the animals seemed vilified for no reason other than being animals; other times there are changes to the creature to give it that “monster” status. The alligator is a mutant or a prehistoric relic lost in time. The sharks’ are really big or their brains have been experimented on. Sometimes it’s as lazy as changing the color of the whale to white. “Look! It’s different from the others, it’s a monster!” Always accompanying these grab bag traits comes ultra aggressiveness. The want, the need, to destroy any human in its path. But this is why you can cheer along with Chief Brody as the shark rains down upon the open ocean.

Some choices make a little more sense than others. Sharks, alligators, lions and bears have all been known to take human life. Accident or not, as rare as it is, it happens. But there are movies out there about killer rabbits, frogs, whales. It doesn’t matter if they have teeth or not. The storytellers will think of a way for them to eat you.

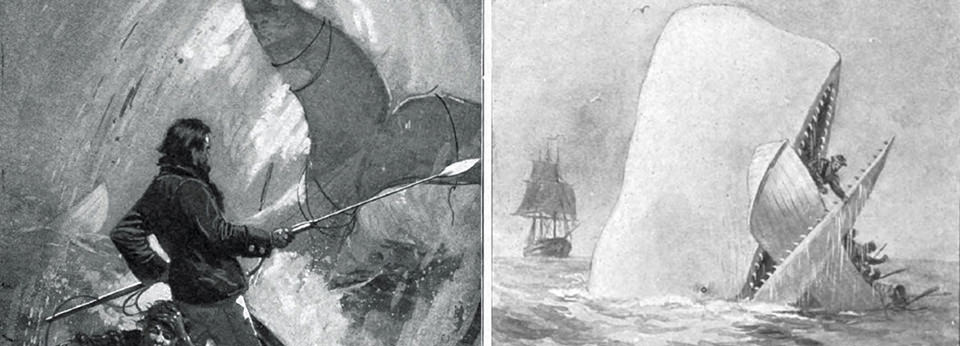

The whale in Pinocchio is named Monstro. They literally named it “Monster.” Subtle. It was a giant of the sea with deadly teeth and terrible eyes, swallowing everything in sight with no remorse. There has never been a verified death caused by a whale in the wild. Four people have died from whales in captivity, three of those were from the same whale! Hmm, maybe not a great idea to keep whales captive. Nevertheless, Pinocchio shows us how terrifying sperm whales are when we’re children. The fear is instilled in us. A sperm whale seems like such a weird choice to make a villain and Pinocchio wasn’t even the first to do it. Moby Dick was written in 1851. We don’t have time to dive into all the meanings behind the story but, on its surface, it’s about a man going crazy at the idea of killing a whale.

Moby Dick is treated as a nightmare beast from beyond but…he’s just a whale. Ahab is out for revenge for losing a leg to the great animal but his leg was taken while he was trying to kill Moby Dick for his blubber. This is exactly what I’m talking about. We’re shown over and over how terrible and dangerous these animals can be but we ignore that so often the humans are the aggressors. Moby Dick is based on a true story but The Essex, the ship in the true story, was sunk by a whale being hunted. An animal fearing for its life. Sperm whales were being wiped out and just one fought back. The whale is not the one at fault here.

Maybe as an animal lover I subconsciously want the animal to win no matter the scenario. So many times the humans are jerks anyway. But what about Jaws? You can’t help but to smile at that look on Brody’s face when he realizes he’s not going to die. Even though Steven Spielberg wanted to keep the shark within realistic dimensions, it’s basically portrayed as an underwater Michael Myers. It stalks and kills in a way that sharks don’t actually do. It’s so unrelenting and terrifying that, when it dies, it feels like you’re finally able to breathe. Look, there are hours of content out there explaining why Jaws is a perfect movie and I’m not going to refute any of it. In fact, it’s so well made that it’s probably not fair for me to even be mentioning Jaws here. Let’s move on.

I’m not saying it’s never okay to kill an animal in movies. I’m not saying there should be rules to follow. If it’s going around acting like a monster and the end result is a dead animal, I can live with that. I can put my bleeding heart aside and enjoy a “monster” movie. If the animal in question is a menace to Amity Islands economy, then sure, kill the shark. If the alligator is eating entire wedding parties, you’re probably going to have to kill the alligator.

But if the animal is only acting out because of the actions of a human and is just trying to exist in its natural habitat, I’m going to root for the animal. In my constant consumption of the genre I’ve encountered a few extremes in both directions. Recently, a few of these extreme examples are what got me obsessing over this topic.

I grew up watching Lewis Teagues’ Alligator. I still have drawings from when I was a kid of the beast and its victims. The animal in this film is a mutant menace. Crashing weddings and destroying city property. It doesn’t matter what real alligators are like because this one is a monster in an alligator’s clothing. This creature hides in swimming pools and eats unsuspecting children. This movie is silly, fun, and ruthless, and the animal is so far removed from reality that it always gets a pass from me. And even though they kill it in the end, they make sure to show us a baby has survived.

Because of this film, I was super excited to read Shelley Katz’s novel, Alligator. Even though there’s no relation to the film, I made the mistake of assuming they would be similar. I bought three copies because I needed the different cover art and had just received the Centipede Press Special Edition. Let me make it clear, I’m not complaining about Shelley’s writing. Her more than competent skills transport you directly into the bowels of the swamp, and when the alligator does have its time to shine, it’s unforgettable. My issue is in the narrative. This book begins with the death of two poachers. Come on, you can’t expect me to feel bad about that, right?

As the story progresses your main characters are a group of rednecks that set out to find and kill an animal of record breaking size. And they succeed. Am I supposed to feel good about that? This creature never goes out of its way to eat anyone. It’s not on a rampage in populated areas, it’s just living its life in the beautiful swamp until men go out of their way to kill it. After 269 pages, when the animal is dead and the poacher is alive, what am I supposed to feel? Is the point of the book that humans suck? If so, point taken.

Or are some storytellers scared to trust the audience to side with an animal over a human being? Am I in the minority? Would most people feel more remorse if the human died and the animal lived even if the human is a walking pile of garbage?

That brings me to the 1977 film, Orca. It gave its main character a sympathetic backstory the book didn’t include so the audience would feel better about the absolute jerk he’s been the entire time. The film erases most of his racist overtones but not his sexism. At one point, he insinuates that he will leave the whale alone in trade for sex. This man not only tries to catch the male Orca, he hangs up its mate and watches her give birth to a stillborn calf on the deck of his boat before leaving the mother tied up to slowly suffocate.

The audience is then subjected to watching the poor male Orca scream in heartbreak and agony as he’s forced to watch. And we’re supposed to relate to this man? Sure, the whale goes on to terrorize a village and a few people lose their life (or limbs) in the process, but it all happens because he was provoked! It’s all because of the actions of Captain Campbell. He’s the real monster here.

The movie, at least, changes the ending and lets the whale exact his revenge, but not before a scene in which our captain explains that he’s going to look the whale in the eye and tell it how sorry he is. Awww, poor captain Campbell.

In 1987 the lesser-known Australian film, Dark Age, delivered the gold standard. It features John Jarratt as a park ranger whose job was to work out what to do with a massive crocodile. The local village’s proximity to a water source puts people in danger of becoming a meal. In one of the most memorable scenes, our heroes are too late to save a child from the brutality of nature. But as a part of nature is exactly how the croc is treated by the locals. They respect it. They realize the animal is just doing what an animal does to survive. Again, the poachers are the true villains in this story.

The film pivots to focus on getting the animal to a safe place away from the dangers of the poachers and far enough away from the village so no one else becomes a snack.

This is how a story like this should be told. I can indulge in the horror and intrigue of seeing a human body become food for a completely apathetic creature and also root for that creature’s survival. More of these movies should have this kind of conclusion.

Most of these specific examples are older works but there’s no lack of modern killer animal movies steadily pumped into our veins. Cocaine Bear also did this right. 95 minutes of a bear eviscerating people, but by the end, you’re rooting for the bear! The animal gets a happy ending even after we watch it rip Ray Liotta’s intestines out.

Ultimately I’m here for every killer animal book/movie. I want to enjoy them all. I just want them to be smart about it. I want to see an animal rampage and absolutely destroy the local human population, but I don’t want to feel depressed if (or when) the animal dies at the end. It’s a balancing act, maybe one that’s easier said than done.

Some might find themselves asking, “why does it matter?” or saying, “it’s just a movie.” Like it or not, as silly as this might sound, some people let movies inform their real life opinions on things. They might take something exaggerated or completely fictional and take it as truth. Research shows that after Jaws was released, there was a 50% decline in shark population. Peter Benchley, author of Jaws, felt so bad about it that he became a conservationist and spent the later years of his life trying to atone. There are probably people reading this that think anacondas are regularly swallowing people but the truth is, that you can buy them at your local pet shop. This places the topic on a whole other level. This is no longer just about making a fun movie, now we’re doing actual damage to wildlife. Is it the job of every storyteller to make sure people know which truth is stretched or made up completely? I don’t think so.

Ultimately it’s on the viewer to do their own research and maybe not take the word of Shark Night 3D. But this is a very real side effect that I don’t think many people think about.

My challenge to you is that next time you find yourself reading or watching an animal making some poor soul its lunch, put yourself in its place. Try to identify the specific traits the storytellers use to change your perception of it. Pay attention to how the humans treat it to begin with. Who’s the aggressor? You might come out of it feeling different about the human protagonists. Or better yet, you might come out feeling different about the animals.